This blog was first published in the spring of 2013.

Swansea has its second chance to lead the world. Will it take it?

206 years ago the city launched the world’s first passenger railway. This week (April 8, 2013) a consortium announced a £10m “investment offering” to fund its proposal to build a “tidal lagoon” in Swansea Bay, to produce enough energy to satisfy the domestic requirements of the city. On this scale it would be another world first.

It’s a diligently-composed plan, introduced through a very professionally made six minutes video on the consortium’s website. Who knows, incidentally, how many airings it was denied on the media by the unfortunate choice of date to unveil it, in a story in the Guardian, the day Margaret Thatcher died?

No matter. There will be plenty more opportunities for Tidal Lagoon (Swansea Bay) plc to persuade local people and politicians near and far that this £650 million scheme deserves their full support.

In common with other renewable energy projects, such as solar and wind, the barrage should not take long to build, an estimated 18-24 months. It could be producing energy by 2020.

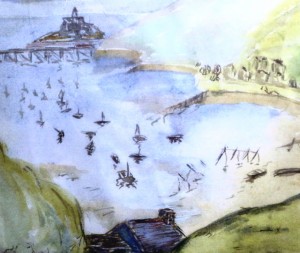

The consortium chose Swansea Bay because it is part of the Severn Estuary, which has the second largest tidal range on Earth. (A second, and much larger scheme there, is been considered.) They propose to build a 9.5km wall 3.5-4km out to sea. There would be an array of hydro turbines at the deepest part of the wall. As the tide passed in and out twice a day, the water would drive the turbines, and generate electricity.

The estimated annual output is 400GWh, which would be fed into the National Grid, producing enough energy to power 107,000 homes.

The project’s backers have to cross several significant hurdles before they can begin construction. First they have to raise up to £10 million to achieve a development consent order, the money partly coming from shares they hope will be bought by local people. Then the scheme needs to satisfy an environmental impact assessment, and gain planning permission from the government. Thereafter it needs bigger, institutional financial backing.

The consortium’s project team – you can see who they are and read their potted biographies on the website – draw up a list of wider benefits. They say the scheme could provide significant benefits to the local economy, by creating jobs both to build the barrages (250 construction jobs), and to make its component parts locally. It would have ongoing revenue-generating power as a tourist attraction. The ambition is for the lagoon to become a major attraction and recreational amenity, stimulating the waterfront economy.

There would be a bicycle way, pedestrian path and perhaps an electric train running along the top of the barrage. The calm waters within the walls would be suitable for yachting, and other watersports. The promotional film anticipates serious sporting contests, one of which could be the triathlon.

The lagoon could also be used for underwater cultivation – mariculture. One suggestion is to revive local production of oysters (Oystermouth is one of the villages on Swansea Bay) and also to grow samphire, to serve the well-established local taste for the fruits of the sea.

It should also help to complete the city’s journey of renewal away from the doubtful status of one of the most polluted industrial cities on earth, when copper smelting works lined the Lower Swansea Valley, and the then town was a major port sending ships laden with the raw materials of industry as far away as Chile and San Francisco.

It could, too, make amends for a long-lamented decision taken in 1960 to tear up the Mumbles Railway, by then the longest lasting passenger rail in the world. What a tourist attraction that might have been today.

The backers cite low technological risk as one of the advantages of the scheme. Tidal barrages have worked successfully elsewhere, principally the La Rance Barrage, on the estuary of the Rance River, in France. The breakwaters and turbines would be constructed using design concepts and construction techniques used in other applications around the world, although they have not been brought together in one development. There would be no rivers emptying into the lagoon, which would be filled only by the tide.

The counter argument is cost. People are being asked to put up the initial cost of up to £10 million to achieve a development consent order. If it is built, it is unclear how soon a scheme like this would be able to compete, without subsidy, with coal-generated power, and the gas the Chancellor believes will flow from the promised fracking revolution.

(La Rance Barrage opened in 1966. The development costs were high but these have now been recovered, and electricity production costs are lower than that of nuclear power generation.)

These and other points are addressed in the usual intense debate in the comments section under the original Guardian article. It seems to me the very quickly delivered environmental benefits, saving over 200,000 tonnes of CO2 a year, the equivalent to 40-50,000 cars taken off UK roads each year, are simply too big to turn down. And, as is increasingly the case with renewables, it’s an project that even climate change denies can support, as our power stations are decommissioned and the case for energy independence becomes even more urgent.

For me, and I must declare an interest as I was born in Swansea, this tidal lagoon would be a fine thing quite apart from all the environmental good it should do. It would add a feature of which Swansea could be very proud, destined to last 100 years. It would bring the city recognition around the world, an elegant extension of Swansea’s splendid curving bay, which Victorian writer Walter Savage Landor compared to the Bay of Naples, and to Dylan Thomas’s “ugly, lovely town”.