An interesting piece in the Guardian by Peter Hain (Lord Hain, the former Labour minister.) He makes a strong case for a halt to all pending trials of Extinction Rebellion (ER) activists, accused of deliberate criminal damage in their attempts to highlight the climate crisis.

An interesting piece in the Guardian by Peter Hain (Lord Hain, the former Labour minister.) He makes a strong case for a halt to all pending trials of Extinction Rebellion (ER) activists, accused of deliberate criminal damage in their attempts to highlight the climate crisis.

Last month (April 2021) six members of ER, charged with criminal damage against Shell’s building in London, were acquitted by a jury in Southwark crown court. The jury handed down the verdict despite the judge ruling that only one of the accused had any kind of defence in law.

Many more trials are waiting to be heard in the courts, arising from action taken by ER supporters mainly in 2019 against oil companies and others connected to the fossil fuel industry.

Hain wrote:

‘The two-week Shell trial at Southwark was a case study in what can happen when environmental activists put their trust in the people. It seems that the law is out of step with the public, and that there could be many more such “perverse” verdicts by rebellious juries.’

What about the argument that people have no right to wilfully damage private property, and the owners of that property have every right to expect redress from the courts, particularly in such clear-cut cases as this? Hain notes that the Shell jury, after hearing the evidence, concluded that the damage done was a proportionate response to the damage Shell continues to do to the planet.

Shell, and the others, have no defence against this accusation, that their products have been damaging the planet, by accelerating global heating, long after their own experts, in the case of Exxon and Shell, told them it would, in reports in the 1980s.

And it wasn’t just internal studies, which may not have been intended for public consumption. Perhaps the most clear example of an oil company thinking the public had the right to know about the dangers of climate change and global heating came, remarkably, as early as 1991.

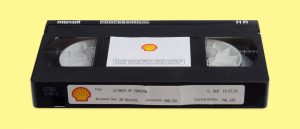

In 1991 Shell issued Climate of Concern, a public information film in which it warned of the dangers of climate change and the need for urgent action. The 28-minute film was made to be screened to the public, and especially to be viewed by schools and universities. It warned of “extreme weather, floods, famines and climate refugees as fossil fuel burning warmed the world.”

According to Shell the climate was changing “at a rate faster than at any time since the end of the ice age – change too fast perhaps for life to adapt, without severe dislocation. Action now is seen as the only safe insurance.”

Shell’s film was unearthed by Dutch news website The Correspondent in 2017. Prof Tom Wigley, head of the Climate Research Unit at the University of East Anglia when it helped the oil company with the film, told The Guardian the predictions for temperature and sea level rises it made were “pretty good compared with current understanding”.

Thereafter Shell shelved those early warnings, and reverted to “business as usual” mode. Together with other oil companies and the media, with some honourable exceptions, it lobbied against strong climate legislation and, with dangerous complacency foretold a much rosier future.

In February (2021) Shell revealed an “accelerated” strategy to reduce oil production and decarbonise its products by 2050. However its revised targets were overshadowed by plans to spend $8 billion a year on oil exploration and gas pumping in the short term, compared with a $2 to $3 billion a year spend on renewables and hydrogen. (https://www.desmog.co.uk/2021/02/11/shell-net-zero-oil-fossil-fuels)