Freiburg in Southern Germany, and the new city of Milton Keynes, 50 miles north of London, are about the same size – populations of 215,966, respectively, against 229,941 in 2022. But in terms of public transport they are worlds apart.

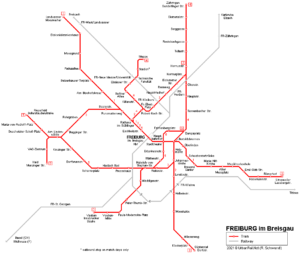

Reduced to the essential detail of how people get about, MK, as it is widely known by locals, has lots of cars and many roundabouts, some of them big and intimidating. Freiburg has trams running almost everywhere; 65 per cent of Freiburg residents have a tram stop within 300 metres of their home.

I want to immediately deflect MK apologists by acknowledging the new city’s many virtues. Public parks everywhere. Abundant tree-planting. A complex and extensive network of cycleways, and pedestrians paths (with underpasses). Lots of electric car charging points. An adequate bus service, with electric buses on one route. And a non-stop train link to London, which takes about 32 minutes.

That’s not so bad, surely, in this brave new metropolis, which is still being built? But the reality is that it’s overwhelmingly attractive to the private car. I know MK well, and I’ve been going there for many years. If someone asked me, objectively, to name the most useful recent addition, in terms of accessing the city centre, I would have to say the spacious new multi-storey carpark behind John Lewis in the central shopping mall. (It’s cheap, too.)

And what of Freiburg, promoted as the sustainable Black Forest metropolis? Public transport and bicycles have long been the prevailing methods of transport. But far and away the prime player is the tram, moving busily through crowded streets like some superior force of nature, with priority at every junction, electric and clean, answerable only to its passengers.

There are trams in many European cities, and large towns, but Freiburg is its apotheosis. It’s the transport of choice here to such an extent that the city has the lowest car density of any city in Germany (423 per 1,000 people). Annual car trips have hardly increased over the last 15 years, even while the total number of trips of all forms has increased by 30 per cent.

Trams don’t go quite everywhere, although the network has to be extended into any new development areas in the city; but where it doesn’t or can’t go there is a well-integrated network of buses, and commuter railway lines.

Trams go everywhere in Freiburg

Anticipating a question here, I accept that the centre of Freiburg was flattened in the war, and had to be rebuilt, and it is easier to start from scratch when you creating a public transport system. So why pick on MK? Yes, but isn’t MK quite the best example of a city began from scratch, in the 1960s?

And before you say other places in the UK couldn’t possibly introduce trams in cramped urban centres, because they weren’t flattened in the war, note that Nottingham (centre not flattened) has a tram, while Swansea (centre flattened) not only doesn’t have a tram, but it got rid of a perfectly good one (Mumbles Railway) in 1960. Underpinning all these public transport choices is local politics, based on an often impenetrable and peverse form of decision-making.

I give the example of Milton Keynes because it is a city of grids and mainly straight lines. It is probably one of the easiest places in Britain to retrofit for tram lines. The required culture shift away from easy car access to all points would be immense, but is the mood changing? Writing in The Guardian (Aug 30, 2022), John Vidal argues that “the worldwide love affair with the car is over…. The reality…is that the car is now a social and environmental curse, disconnecting people, eroding public space, fracturing local economies, and generating sprawl and urban decay. With UK temperatures hitting highs of 40C this summer, this reality has become impossible to ignore.”

For the time being in MK, displacing the car with a fast, mass transit system must remain an aspiration. Meanwhile the Freiburg trams trundle busily on.

Freiburg is about 7 hours by train from Londopn St Pancras. What to see there.