Irongate Wharf, the exact spot where Patrick Leigh Fermor left England in the Stadthouder Willem, as he recounted in A Time of Gifts

91 years ago, on the ebbing afternoon of Friday, December 8th, 1933, a young man of 19, shrugging off a hangover, with a backpack borrowed from a friend, walked under the arch out of Shepherd Market onto Curzon St in the West End of London and hailed a cab.

It was the start of a journey of rare ambition by the carefree Patrick Leigh Fermor, a mix of, mainly, walking, with lifts on boats and other impromptu transports across Europe. His destination was Constantinople, just recently renamed Istanbul.

It would become the classic account of a trek into the heart of a darkening European continent on the brink of war, Yet it’s easy to overlook the exquisitely-drawn prelude, the brief preparations and the short taxi trip in London. In the page and a half of A Time of Gifts, there is enough fine, tight description of a late, and wet, afternoon on the capital, that only the most insensitive reader would not want to follow him on his odyssey over the water.

The London visitor can easily replicate it in an afternoon, or less, on foot, in a taxi or in a bus, or perhaps a mixture of all three, on a route from just off Piccadilly, to Irongate Wharf next to Tower Bridge, from where the writer embarked on the short trip to Holland aboard the Stadthouder Willem for the start of his long walk. He was to begin in earnest the next morning, or technically later the same long December night, for it was still dark when he did so.

Patrick, or Paddy as he was generally known, was a young man straight from school, and a brief job selling silk stockings, walking off into a dark decade. He had no firm ambition, and no record as a writer. Should we be surprised that we had to wait over 40 years for him to tell the story of that adventure? (There was a more prosaic mitigating factor: his diary was stolen half way into the trip, in a youth hostel in Munich.)

When it came, much later, as A Time of Gifts (1977) and Between the Woods and the Water (1986), the mature Paddy was hailed for producing what, still today, is a persuasive candidate for the finest piece of travel writing of our times.

By then he had gone on to distinguished military service, and to kidnap the German commander in Crete, communing with him on the highest, emnity-dissolving level of civilised discourse, sharing each other’s knowledge of Greek poetry. In Paddy’s case this was the product of an intermittently educated but intensely bookish youth. That famous exploit had already been recorded in the film Ill Met by Moonlight.

Paddy died in 2010, the third volume in his account of his walk unfinished. It became the great long-awaited travel book. It appeared in 2013, under the title The Broken Road: From the Iron Gates to Mount Athos, edited and introduced by Colin Thubron and Artemis Cooper.

I began my journey, not where Paddy started his, in Curzon St, but under the Wellington Arch, at Hyde Park Corner. The reason, immense and triumphant, is high above my head, the statue “Peace”. The model for the colossal, half clothed warrior queen, majestic in her chariot, replacing a statue of Wellington in 1912, was Paddy’s landlady, Miss Beatrice Stewart.

In this prelude to a prelude, I walked east for a while across Green Park, to meet the memory of Paddy in busy preparation mode. He had picked up his rucksack, lent to him by the botanist Mark Ogilvie-Grant, in Cliveden Place; he bought a walking stick of ash in Sloane Square, and most of his walking clothes in Millet’s army surplus store in The Strand.

And here he is, hurrying across the park bearing the passport he had just picked up from Petty France – “born London, 11 February 1915; height 5′ 9; eyes, brown; hair, brown; distinguishing marks, none…”

Paddy decided to leave England because of “a sudden loathing of London. Everything seemed unbearable, loathsome, trivial, restless, shoddy…” According to his biographer Artemis Cooper (Patrick Leigh Fermor, An Adventure), his academic career had been a “disaster”, and he had turned against the military career his parents had in mind.

He had, however, been living life quite fully for the past few weeks, drinking in the Running Horse pub (it’s still there, in Davies Street). This is where he gave his amusingly graphic description of what to do with the ladies’ stockings he was selling, pulling one over his head, and was instantly sacked.

I followed him out of Green Park, across Piccadilly and up his “crooked chasm” of White Horse Street, still kinked in the middle as he describes it.

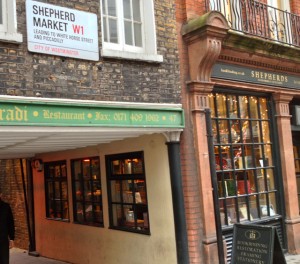

While some places he mentions in that London passage of the book were hit by German bombs in the war, the West End was largely spared. Shepherd Market, where he lived for those last few months, is one of those distinct and intimate little London communities, with a good sense of place, anchored around a traffic-free square. It is much as it was, at least in its essential layout. Many of the shops have changed, but there is a pub or two Paddy would have known.

Exit from Sheperd Market onto Curzon St, where Patrick Leigh Fermor hailed a cab to begin his epic journey to Constantimople

28 Market Street, where he says he lived, doesn’t exist. Did he mean Shepherd Market, or Shepherd Street? Writing so long afterwards he can be forgiven for forgetting. If it was Shepherd Market, that’s now a newsagent’s.

He was in time for a “goodbye luncheon with Miss Stewart and three friends – two fellow-lodgers and a girl”. (Who? He leaves us tantalisingly uninformed.) Then, away.

I turned down Half Moon Street, following the route his taxi took, together with his three friends. (Not today, for a taxi – it’s a one-way street.). From there on today’s cabbie could replicate his journey almost exactly. Once on Piccadilly (“a thousand glistening umbrellas tilted over a thousand bowler hats”), it’s easy enough to weave down through St James’s Street and left onto Jermyn Street. (“Shops, distorted by streaming water, had become a submarine Arcade.”)

It was raining heavily by now, on that long-ago December day in 1933. (Or at least Paddy said it was.) To many writers this would have been no more that another very wet day in London.

Fermor makes it an amphibious voyage rather than a taxi trip, peering out of portholes. I follow him along Pall Mall, over Trafalgar Square (“blown askew, the fountains twirled like mops”) and into The Strand, where the taxi is held up by the throng. I step aboard a 15 bus, which follows his route almost to the end.

Is the surge of commuters he describes delaying his taxi (“Charing Cross commuters reeling and stampeding under a cloudburst”) so different today? No bowler hats, of course. He doesn’t mention Christmas shoppers or revellers or the winter tourists. There would not have been many.

He points to a few few landmarks in this familiar trip, perhaps now with a middle aged writer’s eye. The approach to St Paul’s (“the dome sank deeper in its pillared shoulders”), illuminated in its formidable bulk, is still uplifting, as great buildings often are, as the daylight ebbs on a winter afternoon and the lights come up. I find a perverse charm in a late afternoon in a busy city, as the gloom is partly dispelled by cheer of the brightly lit shops, the colour and bustle.

Paddy’s taxi “slewed away from the drowning cathedral”, and turned right, past the Monument, down onto Upper Thames Street. I leave the bus at Monument and follow him. It’s a few short strides down to two churches he mentions by name – he heard the bells of St Magnus the Martyr and St Dunstan’s-in-the East tolling the hour. Both would be casualties of the war to come.

Within a week or two he would see for himself the distinct cultural switch in Germany, which would lead many people into willing support for that war, as he crossed the paths of the emerging Hitler Youth and Brownshirts, and in conversations with ordinary Germans who were still addressing the novelty of a passionate nationalist as their leader.

One of the things we lose with the books written so much later is Paddy’s contemporary voice – how much did he know of the newly elected Fuhrer when he walked into his first German village, several days down the trail? It was already in the newspapers. As he was crossing the North Sea, the Sunday Times hit the streets with a report of the chief of staff of the Sturmabteilung or Brownshirts denying that they had any “military character”. The writer reminded readers that they often used to be referred to as “Hitler’s private army.”

The lights were bright at St Magnus the Martyr. I walked to the door as the last of the daylight died. The church, washed by the constant sound of traffic, is a landmark painfully familiar to innumerable participants in last few miles of the London Marathon. It stands under sheer cliff faces of office buildings, thrusting its tower defiantly up. It took a hit in the war but was repaired.

A few hundreds yards towards The Tower, German bombing had a more terminal outcome. Never again would the bells of St Dunstan’s-in-the-East ring out. (Which hour they were tolling he doesn’t say. Was it 5, or 6 perhaps even 7. In any event his taxi ride couldn’t have lasted more than 30 minutes.) The medieval church with a Wren tower was severely damaged. Instead of restoring it, its custodians have left it is a benign half-ruin. The hollowed out nave is a garden of peace and ease, much used over the years.

Paddy’s taxi passed the Mint. “Then, straight ahead, the pinnacles and the metal parabolas of Tower Bridge were looming.” The taxi halted on the bridge just short of the first barbican. The driver indicated the flight of stone steps that descended to Irongate Wharf, where the Stadthouder Willem was waiting.

I took the a convenient passage under the bridge, from the Tower complex, its subsequent development for tourism unimaginable in 1933. The river, too, has changed immeasurably since before the war, when commerce extended into the heart of London and the banks were a forest of gantries.

But I managed to find one image to transport us back there. It is is a photograph taken just four years later, in 1937, showing Tower Bridge and Irongate Wharf, in the collection of the Museum of London.

There was no time to lose. Paddy’s companions waved him off, and the ship began to edge into the flow. And then he was away, drifting down the Thames to travel literature immortality.

I looked around for something, anything, to remember this moment. A Portuguese couple were taking each other’s photos at the exact place where the Wharf used to be. They accepted my offer to put them together in a photograph, with the now splendidly lit-up bridge as backdrop. The river, a deep melancholy brown, flowed on.

Footnote.

Paddy was looking back a long way when he wrote the book, and a quick online check shows some hazy meteorological recall, at least for the London section.

There couldn’t possibly have been heavy rain. The Times of the day forecast a mainly dry weekend, apart from scattered showers of sleet or snow over England.

The first snow of the winter fell in central London the previous day. The AA was advising motorists “contemplating journeys to carry skid chains as frost has been forecast.”

Next day The Sunday Times reported that “As far west as Plymouth the temperature in the early afternoon was only 31° (0C). At Kew it was 33° (1C). Light falls of snow again occurred locally.”

Paddy was spot-on about the snow in Rotterdam early next morning, however. The centre of a large anticyclone had moved from Scandinavia to Scotland. There was “a drift of intensely cold air from Eastern Europe.”

Forecasts weren’t as accurate in the 1930s as today, but it’s hard to see how there could possibly have been a cloudburst over the Strand. And it doesn’t matter a bit. Dull, still winter afternoons don’t offer the descriptive writer much to go on, and deluge and tempest was just right for his dramatic opening. If he had stuck to the truth, we wouldn’t have had “The Monument, descried through veils of rain, seemed so convincingly liquefied out of the perpendicular that the tilting thoroughfare might have been forty fathoms down.”