High view of Dublin - from Guinness Storehouse, through James Joyce quotation (A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man)

The best way to begin a visit to Dublin is not with a drink, but inside a drink.

If that sounds too completely barmy even for this city of whimsy and imagination, consider this.

The finest view of the Irish capital is from the glass-walled bar on the seventh floor of the Guinness Storehouse, the visitor centre in the 250 year old Brewery. It’s shaped like a gigantic beer glass. We made up the dense creamy froth on the top of the “pint”.

This place is unlike any other of the many, friendly pubs of Dublin. For once you are not here to talk, but to gaze in silent wonder.

It’s the way to get ahead on your sightseeing. High up and warm, (and free drink in hand – you get a pint of the black stuff for making it to the top) we previewed Dublin’s random marvels, spread out below.

There’s the great green expanse of Phoenix Park – there’s room for four Hyde Parks – speared by the two-mile long tree-lined avenue. To the right, the 300 year old Collins Barracks with its immense central parade ground, one of the biggest in Europe, bordered by arcades. It’s a powerful reminder of British military might, when Ireland island was ruled from London.

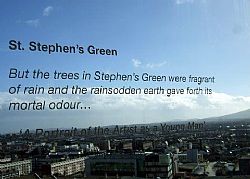

The brewery could be forgiven for slipping in a last reminder of their famous product. Instead they festoon the windows with quotations, linked to specific places in the city, from James Joyce’s accounts of his home city in his novel. Read a sentence in a window, and behind it, somewhere in the view is the place it refers to.

One quote, referring to the Martello tower at Sandycove, to the south of Dublin Bay, is the opening of Ulysses, The book would be the perfect example of novel as tourist guide, if it wasn’t quite so difficult. Joyce wrote in passionate detail about his city: he believed the book could be used to rebuild Dublin if a stray asteroid took it out.

“Reading” the view was just another example of the obvious truth. Dublin is the capital not of the world, as other cities tend to claim, but (far better) of the word, supreme here in all its forms – spoken, written or sung. And the references to writers and their creations are everywhere, from pubs to bridges, from the city’s ten theatres to the newest wing of the airport.

Take just one fabulous statistic, and surely no city of this size can match it. Three of the city’s great writers, George Bernard Shaw, Samuel Beckett and W. B. Yeats, won Nobel prizes for literature.

To bring the prize winning full circle, we were there the day Irish songwriter Glen Hansard won the Oscar for best song, in the movie Once – set, of course, in Dublin. Just another landmark in the long march of Dublin”s music-making, which goes back to the first performance of Handel”s Messiah here in 1742.

We chased writers in a crazy zig zag across this compact city. In the west we found Shaw’s Birthplace, just as it was when the bearded titan left it. In the north, the Writers Museum, to find out about the more unexpected titles to come from Dublin writers, such as Gulliver”s Travels and Dracula.

Under Dublin Castle we found the splendid Chester Beatty Museum. Its beautifully presented display of world religions includes some heart-stopping fragments of early gospels from around 150 AD, and an exquisite little golden Koran.

It was my first visit to Dublin for over 10 years. I”m happy to report that the only thing that’s worse is the traffic. Don’t expect the tourist board to mention it, but the gridlock is dire. Our trip in from the airport (take the Aircoach, €12 return) gave us lots of time to inspect the outer suburbs.

We found consolation in breakfast at Bewleys, on Grafton St. Too new for my guide book, this famous old café, was restored to its 1920s’ splendour in 2006, complete with stained-glass windows and statuary. This is where the writers went for coffee the morning after the pub before. Now it provides perfect salvation for passengers off the red eye flights from the UK. We took the whole deal, the full Irish breakfast (it includes black and white pudding).

You can explore all sorts of themes on a Dublin visit (although there is a good chance they will link in with those writers, singers and talkers). Take the famous doors, one of the most successful promotional images ever used by a city.

To contradict Henry Ford, you can have any colour as long as it isn’t black: we saw green and yellow, red and blue, yellow and cerise. They come single and double, and generally up a short, graceful flight of stone stairs. Some of the best are on FitzWilliam and Merrion Squares. And of course writers lived behind them, notably Yeats and Oscar Wilde, before he left for England.

They date from Dublin”s era of high prosperity, two centuries ago. Too many were lost in the 1950s and 1960s, when Republican sentiment wanted the British legacy flattened. But demolition was halted and today and they sit high on any estate agent’s world list of desirable features.

The famous “30 Dublin doors” poster was based on photographs taken by an American advertising man in 1970. It was turned into a poster, originally from the Irish Tourist Board”s New York office.

We ticked off the best front doors from the cosy downstairs of the Red Bus tours. Only a few hardy tourists, probably from the Arctic, braved the uncovered upper deck. Fitting these vehicles with open tops is stretching optimism to its limits in this meteorologically perverse city.

If you are in a hurry, the “hop on, hop off” circular bus tours are ideal for joining up the many surprises, which include the sudden shock of Dublin”s grand and graceful 18th and 19th Century buildings. In its prime, this was the second city in the Empire after London. It had prosperity to match, and the legacy is scattered randomly around, in such handsome structures as the Four Courts, City Hall and the Custom House.

We found you can’t keep politics out of tourism. After all this country was founded on strife. So even strikingly new things in Dublin, such as the 390 feet high Monument of Light – it looks like a silver tin tack – on O”Connell Street, built in 2003, has its roots in the past

The slender cloud-piercing protuberance, commissioned as part of O”Connell Street’s makeover, is where Nelson”s Pillar used to be. Nelson”s mistake was not to be Irish, unlike Wellington ( a massive obelisk in his name still stands proud in Phoenix Park). So the IRA blew him up in 1966.

After some very shabby decades, O”Connell Street, one of the widest avenues in Europe, looks smart again. The newest attraction is the street installation by Julian Opie, who has designed stage sets for Dublin based rock band U2. It features Sara, Jack, Julian and Suzanne, four life-size computerized walking figures, on LED screens. There’s a life size dancing figure around the corner on Parnell Square. Opie’s idea is to take the pomposity out of art, and make it part of everyday life.

Perhaps the most poignant sight in Dublin is the huddle of statues of forlorn famine victims trudging before the Custom House. The Irish Famine is also remembered in song. If Ireland are winning in rugby at the new Aviva Stadium, the massed ranks will break into “The Fields of Athenry” , an emotionally laden ballad about those events of the 1840s.

But back to the writers. Our hotel was Jurys Inn Custom House, on the restored old docklands area in the Liffey’s north bank, and a ten minute walk from the craic. We took the Sean O”Casey pedestrian bridge across to City Quay. It’s named after the writer of Playboy of the Western World, and is the third new bridge over the Liffey in the past five years.

Apart from the unimaginatively titled (for Dublin) Millennium Bridge, near the old pedestrian Ha”penny Bridge, all bridges here now seem to be named after writers. Indeed the James Joyce Bridge points straight at the house where the writer set his short story ”The Dead”, in Dubliners . It was made into a movie, the last film directed by John Huston.

Dublin newest crossing, the Samuel Beckett Bridge, opened in 2008. Appropriately it is in the shape of a harp lying on it’s side, waiting to be played. This being Dublin, somebody probably will.

We sat in a window seat at Fitzers restaurant on Temple Bar Square. This is one of many good examples of a distinctive Irish cuisine in the city. Between courses we enjoyed that relatively new Dublin attraction, the paper bag parade, in the street outside.

While Britain dithers over plastic bags, Ireland decided to charge people for them in 2002. It did not bring the end of shopping as we know it. From our window seat we watched the shoppers pass. Most carried their purchases in a paper bag. Square, robust and colourful, paper has become a minor fashion item. It doesn’t sag, like plastic. One small blow for the environment. Ireland should be proud.

The smoking ban is something else they did well before us. It has made places like the Market Bar, a vast luminous warehouse of a gastro-pub – and glory be, no canned music – very attractive to non-smokers. It’s a high shed of a building, with spaced out tables, big pot plants, masses of wood, and a high mirror behind the bar. One wall is composed entirely of niches containing shoes. They serve you tapas where you sit. And wine from a big list

The last thing we saw on the streets of Dublin was a group of busking teenagers, next to the statue of Molly Malone. What will become of them? For being brave enough to take on the whole of Grafton Street without even a microphone, I reckon the next U2, at the very least.

On the bus to the airport we caught one last excerpt from Dublin’s glorious past, the gracious, floodlit Bank of Ireland building, built in 1729 to house the Irish Parliament. Paris, Rome and Vienna don’t do things much grander

Normally that is it, when you depart to catch the plane. But Dublin had one last surprise. The Irish Writers’ Gallery, at the airport’s new Pier D, celebrates 12 of Ireland’s most eminent scribes. A laminated glass portrait of an author, with a quotation from his or her work, stands at each boarding gate.

Samuel Beckett’s image, with a snatch from “Waiting for Godot” saw us off for our flight. The word reigned supreme, all the way to the departure gate.